What Admissions Seek

From Behind the Curtain: What Admissions Officers Really Think (and How It Should Change How You Apply)

When you submit your college application, what happens next is partly mystique and partly machinery. In this post, I’ll pull back the curtain on what admissions officers actually consider, how they process large volumes, and what your student (or you) can do to align better with that hidden workflow. This isn’t speculation — it’s grounded in published reports, surveys, and academic/lab studies of admissions processes.

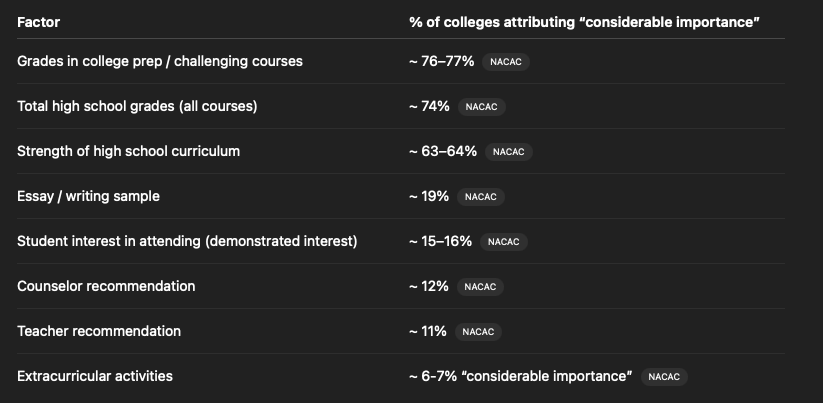

1. What Factors Actually Matter — and How Much Weight They Carry

One of the most helpful data sources is the NACAC “Factors in the Admission Decision” survey (Fall 2023) of U.S. four-year colleges. It shows how admissions professionals self-report the importance of various components. (NACAC)

Here’s a useful distilled ranking (for first-time freshmen):

A few takeaways from that:

Grades + course rigor dominate: Even in the era of holistic review and test-optional policies, academic indicators remain foundational.

Soft factors (essays, recommendations, activities) are not ignored, but often act as tiebreakers or differentiators among similarly “qualified” applicants.

“Demonstrated interest” (e.g. campus visits, email engagement, showing you want to attend) is considered meaningful by many institutions, though less heavily weighted than core academics.

2. How Applications Are Processed — At Scale

Understanding how admissions offices sift applications is just as important as what they look for. Here’s what the literature (and admissions insiders) reveals:

(a) Multiple Readers + Triage + Committee

Most applications are read by at least three different admission staff members, each offering comments or scores.

Applications that clearly exceed standards may skip further review (i.e., “fast track” to admit).

Many “maybe” or borderline applicants go to a committee discussion or deliberation before a final decision is made.

In committee settings, readers will highlight distinguishing features (e.g. “this student did X research,” “that student showed leadership in Y,” or “this resume ties into the school’s mission”).

(b) Speed & “First Impressions” Matter

From former admissions officers’ accounts we learn:

A reader may skim or speed-read dozens of applications per day. The opening lines of the essay or the first few bullet points in extracurriculars carry heavy weight because they need to “catch” the reader.

If an application is weak in one quadrant (say, extremely mediocre grades) but outstanding in another (say, a unique project or publication), it might still be pulled forward if that element is compelling enough.

(c) Predictive & Algorithmic Tools

One of the more recent trends is the use of predictive analytics, machine learning, or scoring systems to help admissions offices filter or triage applications.

Colleges use data on prospective students’ behavior (e.g. web visits, email opens, interactions) to estimate yield likelihood (the probability that, if admitted, they will enroll).

In more advanced research settings, models like CAPS (Comprehensive Applicant Profile Score) attempt to combine academic score, essay quality, and extracurricular impact in a transparent, interpretable way.

Some studies evaluate whether textual data (essays, recommendations) can replace or augment protected attributes (like race, gender) in predictive models. One finding: excluding protected attributes worsens prediction of underrepresented minority admissions unless textual data is included — but textual data doesn’t fully substitute the lost performance.

Caveat & ethical challenges: These systems can be opaque to applicants, and their fairness must be audited (especially given bias risks). Some institutions are now required to disclose or audit automated decision systems.

3. What Admissions Officers Hope to See — From the Inside Out

Beyond data and filtering systems, interviews with former admissions officers and advisors reveal recurring themes in what resonates most:

A clear narrative or theme across academic choices, activities, and essays — not a jumbled “Swiss army knife” profile.

Authenticity over polish: “Genuine voice, not artificial boasting,” especially in essays.

Evidence of growth over time (e.g. improving grades, stepping up responsibility in extracurriculars).

Impact, not hours: Many students log 500+ hours in many activities; what matters more is what changed (for others, for the community).

Context matters: Admissions officers flag that it’s unfair to compare a student from a resource-limited high school directly to a student from a magnet or highly privileged school. The student’s narrative must show how they maximized within their context.

Demonstrated interest & alignment with mission: On committee review, a student whose goals or interests align well with the institution’s values or niche (e.g. a research university looking for future STEM leaders) may stand out.

Polish & coherence: Typos, disorganized essays, or contradictory statements (e.g. claiming you want to major in biology but your activities are in performance arts) harm credibility.

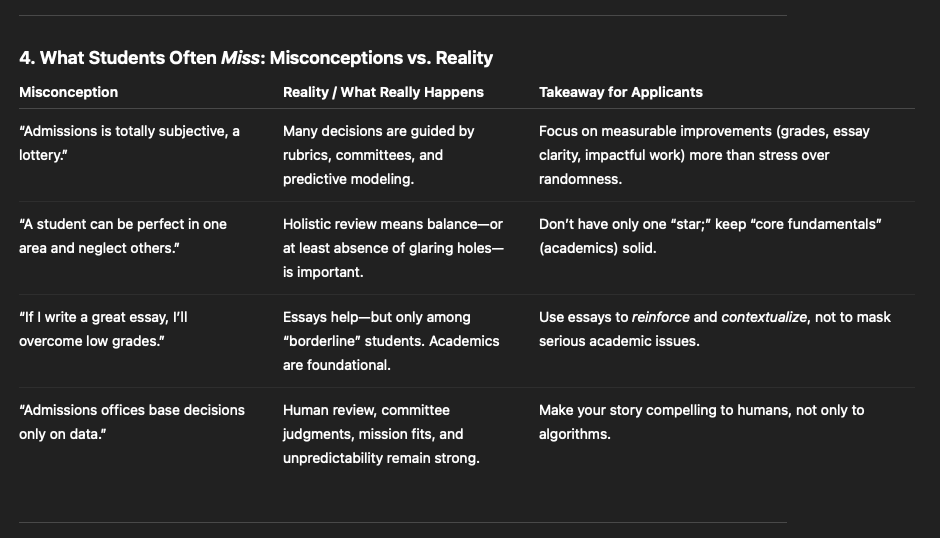

4. What Students Often Miss: Misconceptions vs. Reality

5. Strategic Tips from the Inside for Strong Applications

Based on how actual admissions machinery works, here are actionable strategies:

Front-load your strongest content.

Don’t bury your remarkable activity, award, or personal hook deep in your essay or résumé. Let it appear early so it draws the reader in.Tell a unified narrative.

Use your academic choices, summer projects, leadership, and personal experiences to reflect a coherent vision (e.g. “renewable energy,” or “community health,” or “education inequality”).Show growth, not just accumulation.

Admissions officers notice if a student’s trajectory is rising (e.g. improving grades, more leadership, more independence).Contextualize challenges or constraints.

If your school didn’t offer APs, or family obligations limited extracurricular involvement, briefly contextualize—but don’t use it as an excuse.Selectivity in activities > volume.

It’s better to deeply engage and lead in two or three meaningful areas than superficially join ten.Beware of template essays / AI overuse.

Given speed reading and algorithmic filtering, essays that read like generic templates may blend in rather than stand out.Use demonstrated interest thoughtfully (if accepted by the school).

Engage with campus events, information sessions, and meaningful emails—but don’t overdo it.Polish last, proofread always.

Minor errors can erode trust. Enlist mentors, counselors, or readers for multi-pass proofreading.

6. Why This “Inside” Knowledge Changes How You Prioritize

Knowing how decisions are made means you can:

Allocate your time and energy more strategically (focus on GPA, course rigor, then essay polish, rather than spreading thin over dozens of minor activities).

Minimize wasted effort (e.g. don’t obsess over legacy or prestige when fit, narrative, and context will carry more weight).

Help students better understand why a rejection or acceptance happened (it’s rarely about one “mistake,” more about how the whole package resonated in a specific admissions cycle).

Adjust strategy: for example, if a student has strong academic metrics but weak narrative, they might benefit more from improving essays and strengthening context than chasing extra awards.

Final Thoughts

Admissions isn’t magic, but it is complex. Students who assume the process is random or unknowable often waste energy on distractions. Those who understand what admissions officers really see, how reading happens in practice, and how narrative + metrics combine will apply smarter, not harder.